In This Article

Europe is once again discussing the return of manufacturing – shorter supply chains, greater autonomy, and reduced dependence on Asia. Yet behind this ambition lies a question that is rarely stated openly: how can a continent with high energy costs, limited natural resources, and expensive labour compete directly with Asia’s industrial hubs? For the future of European manufacturing, the challenge is immense. Asian manufacturers benefit from cheap energy, vast production zones, scale, and labour markets that are orders of magnitude larger. At the same time, the United States has opened a new front in the competition for industrial capacity through massive subsidies under the Inflation Reduction Act, drawing European capital across the Atlantic.

Even with tariffs and subsidies, the cost of producing mass‑market goods in Europe remains significantly higher. Importers face a predictable choice: source locally and accept minimal margins, or buy from Asia and remain competitive. Consumers show limited willingness to pay a premium based solely on geography. And governments cannot indefinitely bridge the gap – subsidies rely on tax revenues and borrowing capacity, both under pressure in an ageing Europe.

This is not a temporary market distortion but a structural reality. Reshoring is not a return to the industrial model of the past – that model is economically impossible. Instead, Europe is attempting to build a new one, where automation and AI compensate for the continent’s weaknesses rather than conceal them. The goal is to redefine European manufacturing for the 21st century. Europe cannot outcompete Asia on cost or scale. But it may attempt to compete through architecture – if it can build it in time.

The practical applications of these strategies will be a major highlight at the Hannover Messe 2026.

The Structural Problem: A New Reality for European Manufacturing

While Europe debates reshoring, Asia continues to expand its industrial advantages. The divergence between the two models is not the result of short‑term fluctuations but of deep structural factors. Asian economies combine cheap energy, access to critical raw materials, large labour pools, and industrial zones capable of producing at scales unattainable in Europe.

The current state of European manufacturing operates under very different conditions: high energy prices, limited resources, and a regulatory environment that increases costs at nearly every stage of production. Even the most efficient European factories struggle to match the cost levels of China, Vietnam, or India. This is not due to a lack of innovation or managerial competence, but to a fundamentally different economic geometry. Europe is an expensive continent trying to maintain industrial capacity in a global environment dominated by low‑cost, high‑scale production.

These differences set clear limits on what reshoring can achieve. Europe can shorten supply chains, reduce dependence on specific regions, and strengthen strategic sectors – but it cannot replicate Asia’s mass‑production model. The competition has never been symmetrical, and for European manufacturing, it cannot become so.

Why the Market Cannot Deliver Reshoring on Its Own

Market logic naturally directs production toward regions with lower costs. Importers choose suppliers that keep them competitive; consumers choose affordable products; companies optimise their supply chains based on cost, not geography.

Even with tariffs and incentives, the cost gap remains substantial. This means reshoring cannot be left to the market. It requires political intervention – subsidies, regulations, strategic funds, and industrial policy. But these tools have limits. Europe often compensates for its lack of scale with regulatory power – the so‑called Brussels Effect. Instruments such as the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) are designed not only as climate policy, but also as a way to level the playing field for European manufacturing against producers operating under looser environmental standards.

European governments operate with constrained budgets, high social spending, and ageing populations. Tax bases are shrinking while demands increase. In this context, the long‑term financing of industrial subsidies is limited. Reshoring can be supported, but it cannot be fully funded by public money. This places Europe in a difficult position: it wants to reduce dependence on Asia but lacks the resources to rebuild mass manufacturing. As a result, reshoring inevitably focuses on a narrow set of strategic sectors.

What Europe Is Actually Trying to Bring Back

Reshoring in Europe does not mean bringing back all manufacturing. The continent cannot produce mass‑market goods at competitive prices. Instead, efforts concentrate on sectors with strategic importance for the European manufacturing landscape:

- Batteries and EV components

- Semiconductors

- Medical equipment

- Industrial machinery

- Energy technologies

- Critical materials and recycling

This is reshoring of the “important things,” not reshoring of everything. Europe aims to control key segments of value chains that determine its future economic and technological independence. It is a more realistic approach, but also a more limited one. It does not solve the problem of mass production, but it reduces the risk of strategic dependency.

The New Model: Automation, AI, and the Future of European Manufacturing

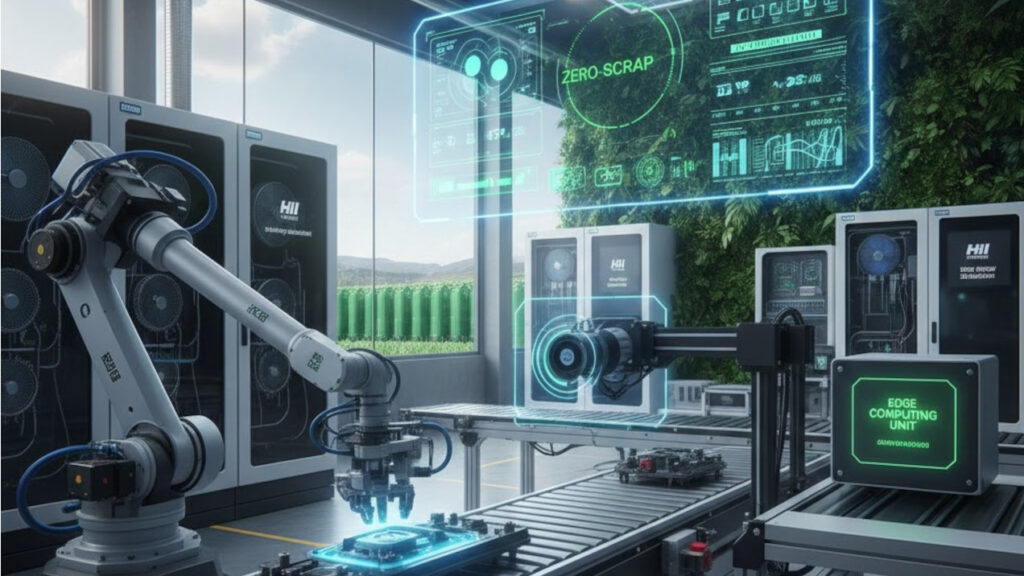

Since Europe cannot rely on cheap labour or scale, it is attempting to build a different industrial model. This transformation is the core of the new European manufacturing strategy, resting on three pillars:

1) High automation: Factories with fewer workers and more robots, reducing labour costs and increasing predictability. This transition is not just about robots, but about a wider automation of production that aligns with sustainability goals.

2) AI as the operating system of production: Algorithms that optimise planning, logistics, maintenance, and risk management.

3) Proximity to the customer: Shorter supply chains, faster delivery, and reduced exposure to global shocks.

The emerging battery gigafactories in northern Sweden – built around renewable energy, automation, and proximity to European carmakers – illustrate what this new model looks like in practice. They are not replicas of Asian megaplants, but regionally integrated, highly automated facilities designed for resilience rather than scale. This model does not attempt to copy Asia but to bypass it through a different architecture. It is more expensive to build but potentially more resilient – if implemented in time.

The Limits: Can This Model Scale?

Despite its potential, the new model for European manufacturing faces several constraints:

- Europe lacks enough engineers and technicians

- Automation requires large upfront investment

- Energy costs remain high

- Raw‑material supply chains remain global

- Competition with US subsidies is intense

- Demographic trends limit growth

Solving the talent gap is crucial, as the industry moves toward a hybrid industrial workforce where humans and AI collaborate.

These factors raise questions about Europe’s ability to scale the new model quickly enough to reduce dependence on Asia in critical sectors.

Beyond Reshoring: Europe Is Not Going Back – It Is Trying to Invent Something New

Reshoring in Europe is not an exercise in nostalgia but a response to a geopolitical and economic landscape that has shifted irreversibly. The continent cannot revive the industrial model of the 20th century – its costs, resources and demographics no longer support it.

What Europe can build instead is a different kind of industrial system: more automated, more flexible, closer to the customer and more dependent on software and AI than on labour or scale. This shift defines the evolution of European manufacturing. It will not make Europe cheaper than Asia, but it may make it more resilient.

Whether this transformation succeeds is uncertain. It demands time, investment and political consistency. Yet the alternative – deeper reliance on external manufacturing hubs – carries far greater risks. Europe cannot match Asia on cost, resources or scale. But it may still compete through architecture – if it can construct that architecture fast enough.